- Home

- Supriya Kelkar

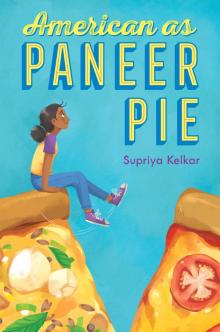

American as Paneer Pie Page 2

American as Paneer Pie Read online

Page 2

One more turn and tap on the pool wall. It was breaststroke time. My biceps burned as my arms went forward, sideways, and down, faster and faster, until I tapped the edge of the pool.

This was it. Freestyle. I turned my head from side to side, arms whipping the blue. It was time to look. I glanced to the side. Harper was right in front of me with a good lead, thanks to her backstroke and breaststroke. I ignored the pain in my legs and zipped forward, my hand in line with hers, seen briefly through the foam. I sliced into the water, faster, almost dissolving into the splashes until I finally tapped the edge.

I pulled my goggles off and glanced at the scoreboard. My name was in the middle of the alphabetically arranged kids. Lekha Divekar: 1:09.30. My fastest time ever.

“We tied!” exclaimed Harper from my left.

I scanned the scoreboard. Harper Walbourne: 1:09.30. She was right. We had tied. Although it may not have seemed like it in school, the way kids flocked to Harper but avoided me, she and I were equals. We had both made the swim team.

I grinned at my parents, who were clapping in the stands as Noah took picture after picture, and then turned to watch Liam finally tap the edge. He was five seconds slower than me. I watched as he stared at the scoreboard and saw his numbers. And as awful as it was, as horrible as it made both versions of me sound, I couldn’t help but feel a little good inside when the smile was wiped off his face.

Because for once, it meant no one was laughing.

chapter THREE

Back home from my triumphant swim, now as a member of the Dolphins, I listened to a song from the old Hindi movie Dangal on repeat as I got dressed for Halloween. The singers roared about believing in yourself and ignoring what others say, because your day will come. I bopped my head along, zipping up an old warm-up suit and squeezing a dry, too-tight swim cap on. I twirled to hit the stairwell lights and danced down, unbothered by the whistles of the pressure cooker that were shouting over my song.

“When will Dangal stop repeating?” asked Aai, before dropping a stack of papers on the kitchen table at the end of our small hall. She preferred soft, classical sitar music over blaring Bollywood hits.

“When I’m done celebrating,” I replied, flexing my muscles.

She smiled, putting down the paperwork Coach had given her after tryouts, and headed to the stove. “Your costume looks great. You’re going to have so much fun tonight.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Just don’t follow us too closely, please?” Aai used to let me walk to elementary school with Noah because it was at the other end of our neighborhood. She didn’t mind me walking down the street to the post office. But she drew the line at Halloween. Trick-or-treating started at 6:00 p.m., and by the end of October, it was already dark then.

Aai nodded, opening the pressure cooker. The nutty aroma of the cooked lentils and the fragrant basmati rice drifted through the house. “You’ll have to make sure your homework is done on time the days you have swim practice. And every third Saturday of the month is a swim meet. Meets start in December for the new kids.”

“I always finish my homework on time, don’t I?” I barely talked back to my parents, respected my elders, got all As, didn’t lie, and didn’t get into trouble at school. I had checked all the boxes on the good-Desi-kid list, I thought as I danced back toward the stairs and entered the den.

I was greeted by the rich smell of the curry leaf plant growing in one of the many pots in the room that made up Dad’s Jungle. Dad was crouched on the floor, gently scooping up some ants that had made their way in for the winter with a cardstock flyer from the mail for Juan Sharpe, the guy running against Winters.

“Lights, Lekha,” he said, concentrating on the bugs.

I reached my hand back out through the door frame and hit the switch, turning off the lights above the stairs behind me, which I had accidentally left on. I knew what was coming next.

“What do you think it is? Diwali?” Dad grinned.

“Hilarious,” I said. After the four-hundredth time hearing his joke about the festival of lights when you purposely turn on every light in the house, it was hard to fake-laugh. I stepped back into the Jungle. The citrusy scent of lemongrass wafted by from one pot, immediately followed by the floral perfume of the tiny white jasmine flowers nearby. I rounded the shelves that housed the plants and turned the music down on the computer in the crowded den.

Dad handed me the dustpan he had dropped the ants into. “You’re not too famous to show these ants out, are you, Michael Phelps?”

I grinned and shook my head, walking past more canvas prints of pictures Dad had taken in India. There was the Sikh Golden Temple, an intricately carved Jain temple, and the Hindu temple my mom had grown up going to.

“And I’ll get the camera. Almost time for pictures.”

I headed out to drop the ants in the front yard. I glanced at the dentist’s house. The towers of moving boxes were now gone, but no new neighbors were in sight. I shivered as a fall breeze coiled around me, making the ghost dangling from our porch roof dance. It wasn’t too cold yet for the little black ants, though. They were still crawling around on the plastic pan, not curling into little frozen balls like they did in winter.

To my right, Mr. Giordano was on a ladder, cleaning leaves out of the gutter. I saw him raise his eyebrows as I emptied the dustpan in the grass. He probably thought I was tossing trash there. I wanted to explain that we were vegetarian and didn’t kill bugs, so instead, we caught them and put them outside. But I thought his eyebrows might fall off his forehead if he heard that.

To my left, Noah in his sharkphin hat, trick-or-treat bag in hand, was heading over to my house with his parents. They were armed with a ton of cameras, cell phones, and camcorders. My parents joined us, and Aai handed me a pumpkin-shaped cloth bag as Noah and I took our places in front of the garage door.

We knew the routine well. Dad took his photography seriously and loved the way the last rays of light hit the garage door in the evening.

“Oh, you two!” Noah’s mom beamed as we smiled for picture after picture. “Don’t ever let the world take those smiles off your faces,” she added, blinking back tears as she crossed her arms over her shirt, which was printed with the union logo I recognized from when Aai worked as an engineer at the transmission plant.

I scrunched my nose at Noah as the sun dipped below the horizon. He just shrugged. Clearly, he got his love of dramatic writing from his dramatic mother.

Before Mrs. Wade could burst into tears, the storm sirens went off across town. Only, they weren’t to warn us about a storm tonight. They were signaling the start of trick-or-treating hours.

“It’s time!” I shrieked, like I was already sugared up.

“You kids have fun,” said Dad as Noah and I ran down the driveway.

First up on our route was Mr. Giordano, but he always gave out pennies in between grumbling to us about the weather, so we decided to skip him. Besides, he was busy cleaning the gutter still and seemed to have no interest in giving us anything other than dirty looks.

I glanced back at our house. My mom-bodyguard was standing at the bottom of our driveway, waiting to follow us. Maybe she would actually give us a couple of houses’ distance this time, since we were eleven.

Noah and I ran up to the next neighbor’s house. They had turned their entire front yard into a graveyard, with robotic skeleton hands waving in the ground and their family names on all the tombstones.

I imagined how Aai would click her tongue in disapproval at the neighbors putting their actual names on the tombstones. My mother was insistent that words had power, and you shouldn’t put bad thoughts out into the world because they would come true.

Since we were two of the few kids on the street still into trick-or-treating, the neighbors loaded our bags with candy. But about half had gelatin in it. I sighed. Gelatin meant animal parts. Animal parts meant I couldn’t eat them. I’d have to give all those colorful, chewy candies to Noah.

We ran house

to house, my legs feeling numb from either the cold weather or the fact that I had swum my best time earlier that day.

“Did you notice the boxes are gone?” huffed Noah as the cold air made it a little harder for him to breathe, even with his pink puffer jacket on.

I slowed down, keeping pace with Noah for the next house. “Yeah.” I nodded. “But I bet they don’t have kids.”

“My sources say it’s a girl,” said Noah, knocking on the next door. “Our age.”

I gasped, and it wasn’t just from the gigantic candy bars this house was handing out. Our new neighbors had a girl! And she was our age! I was finally going to have a friend for sleepovers, right across the street.

Most Desi kids I knew in Detroit had jam-packed weekends, full of Bharat Natyam classes, Bollywood dance classes, classical Indian singing lessons, and nonstop social events, with dozens of holiday celebrations, temple outings, Bollywood concerts, classical music concerts, and Marathi plays added to the mix. They probably barely had time for sleepovers. But we were nowhere near Detroit. And there were zero Indian people here, so zero social events and plenty of time for sleepovers. Just no friends interested in them. But now, with our new neighbor, there was finally hope.

“Are you sure it’s a girl?”

“My dad said he saw a girl carrying a box.”

“Why isn’t she out trick-or-treating?”

“Maybe they don’t know about Halloween.”

“Who doesn’t know about Halloween?” I wiped at my nose as the cold air chilled it.

Noah shrugged. “Or maybe they don’t believe in it. Or maybe they couldn’t find the box with their costumes in it on time. Or maybe—”

“Or maybe they just don’t have kids,” I said again, my arms now sore from lugging my bag full of candy. I didn’t need to get my hopes up unnecessarily. Even if the new neighbor was a girl our age, chances are she’d be more like Harper than like me.

Noah looked at me. “Let’s find out.”

“What?” I asked, shivering. My swim cap was clearly not cut out for Michigan in fall. “I’m tired. Let’s just go home and stuff our faces with candy before dinner.”

“Let’s ring the bell. It’s Halloween. And with the dentist gone, we know they won’t be handing out little toothpastes. So we might get something good. Besides, we’ve done almost every house on the street. Let’s just finish this one and then go home.”

“If they can’t trick-or-treat because their costumes are still boxed up, what makes you think they have candy?”

“Come on,” said Noah, tugging at my arm as he turned up the new neighbors’ driveway.

“Lekha!” Aai shouted from behind us. “They’ve just moved here. Give them some time to unpack!”

I cringed. Aai didn’t have much of an accent, but she did have one. And screaming down the street with it in public was embarrassing even if no one else was around to hear it but Noah.

Noah stopped. “Their porch lights are off. Their hallway lights are off. Maybe your mom’s right.”

Aai was not right. I was eleven. I didn’t need a chaperone to trick-or-treat on our own street. I needed some space. It was now my turn to grab Noah’s arm. “Hurry up before my mom catches up.”

Ignoring Aai’s shouts, which were now growing louder as she speed walked toward us, we bounded up the driveway. I punched the doorbell with my finger as Noah knocked loudly on the glass and we both shouted, “Trick-or-treat!”

The door abruptly opened. And so did my mouth. Because the person who answered the door, without a costume on, was a girl our age. But she wasn’t just a girl our age. She had silky black, shoulder-length hair. Her skin was brown. She was Desi.

I couldn’t believe it. Another Desi family in our tiny little town! There would finally be someone to get it. To know what it’s like to feel different but want to be the same as everyone else. To love your Hindi movie star posters all over your bedroom wall but to be mortified when a teacher asks you to say a word in Hindi. To know how it feels to be asked once a week where your dot is, or if you shower, or if your parents can speak English. To know what it’s like to have two lives, your Indian life at home and your American life at school.

I smiled bigger than I had all day, even after making the Dolphins. “Hi! I’m Lekha, and this is Noah.”

The girl smiled. “My name is Avantika. It’s so great to meet you.”

My smile curled slightly down at her words, and it wasn’t because I could hear Aai’s footsteps getting closer. It was because I was wrong. My new neighbor wasn’t exactly like me, and she probably didn’t know what it was like to feel everything I did. My new neighbor had a thick Indian accent. My new neighbor was a fob.

chapter FOUR

I’m a fob too,” said Dad from behind the kitchen counter as he squeezed a cheesecloth until a light-yellow liquid came out of what was wadded inside. “Fresh off the boat.”

I was eating my Halloween candy out of the bag, but my thoughts were on what Dad was making. As he unwrapped the cloth, revealing the clumpy white paneer inside, I chewed faster. It was partly because I didn’t know if my parents were going to make me hand over what little candy I had left after the great gelatin purge to make Avantika feel welcome here. And it was partly because I was starving; the Indian cheese was one of my favorites, and Dad made it really well.

“You are not a fob,” I replied, watching as he formed the cheese into little cubes in preparation for the big dinner he and Aai had planned for our new neighbors. “Your accent isn’t that thick. You came here a long time ago. You know how things work around here.”

Dad made a disapproving clicking noise with his tongue.

“I feel so bad for anyone who has just come from India. You kids act as if you’re better than them,” said Aai from the kitchen table. She was chopping up tomatoes and garlic, adding them to a bowl with some mint leaves from the Jungle.

“She’s right,” said Dad, heating up some oil in a cast-iron pan. “You guys just laugh at the accents of anyone from India, thinking how funny it is to hear someone say a word differently than you do. But what you should be thinking is, ‘Wow, that person can communicate in at least two languages.’ Something you can’t do, can you? Or should we ask your aaji?”

I cringed, thinking of my conversations with my grandmother in India. I used to speak Marathi when I was a little kid, but I quickly gave it up once I started elementary school at Oakridge. Even though I still understood Marathi, I could barely speak it now. My accent was so thick, I could barely say the r right, and everything sounded funny. So, every weekend during our calls to India, I’m forced to have the same conversation with Aaji. “How are you?” “I’m fine. How are you?” “I’m fine. How are—” and then I hand the phone over to Dad, my ears burning red from embarrassment.

“Do you have any idea how hurtful it must feel to people new to this country to be made fun of just for being Indian? You’re lucky you didn’t ever experience that.”

I stopped shoving chocolate in my mouth, suddenly feeling more annoyed than hungry. If only Dad knew just how often I got made fun of just for being Indian.

“And by a fellow Desi, too,” said Aai, bringing the tomatoes and garlic to the pan and tossing them in. “If you call them fobs, they can call you ABCDs and you can’t complain.”

“Nobody says that,” I retorted over the crackling of the oil.

“Sure they do. ‘American-Born Confused Desi.’ Doesn’t that sound like you?” asked Dad, sliding the paneer cubes into the sizzling oil.

“Okay,” I said, starting to feel a little guilty. “I get it. I won’t say that word again. It’s not nice.”

“And it’s not right,” added Dad. “This is America. There are people from all over the world living here. You’re not more American than Avantika. If that’s the case, then Noah’s more American than you because his grandparents immigrated here, not his parents.”

“Well, he kind of is,” I said.

Dad shook his head. �

��No. He isn’t. That’s not how it works.”

“Nobody is looking at me, and definitely not at Avantika, and saying, ‘Oh, she’s as American as apple pie.’ ”

“You’re as American as … as paneer pie,” Dad said, turning the cubes in the oil.

“Well, that doesn’t make me feel great. Paneer pie doesn’t even exist.”

Dad sighed. “My point is, you’re both American. You don’t have to look a certain way or sound a certain way for that to be true.”

“Like after the flood in the Carolinas,” said Aai. “When that temple opened its doors to all the victims, feeding and housing them. Remember that story in the International Indian News? Those people who always assumed anyone who looked a certain way was bad were suddenly seeing us differently. They even called the Indians there patriots, remember?”

I nodded, not sure what that had to do with our new neighbors.

“So don’t be the C in ABCD anymore,” said Dad, laughing at his own joke.

“As long as you promise not to make paneer pie,” I said, patting Dad’s shoulder. “It sounds disgusting.”

* * *

By the time the doorbell finally rang, I had finished off a lot of my candy and stashed the rest in the cupboard. I hoped that with it out of sight, my parents wouldn’t remember to offer it to anyone. Dad opened the door, welcoming Avantika and her parents, Deepika Auntie and Vikram Uncle, into the house for dinner.

Every grown-up was an “auntie” or “uncle” to Indians. It made things easy when you forgot someone’s name. But I had a feeling we would be seeing a lot more of this particular auntie and uncle, so I made sure to say their names in my head over and over so I wouldn’t forget.

Deepika Auntie, short with sleek hair that she wore tied half up with a gold clip and then braided together just below her shoulder, gave me a huge hug.

American as Paneer Pie

American as Paneer Pie