- Home

- Supriya Kelkar

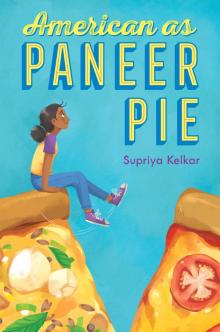

American as Paneer Pie Page 5

American as Paneer Pie Read online

Page 5

“This is Lekha,” added Harper, pointing to me. “She just made it too.”

I gave a friendly nod and quickly tugged at the front of my cap, making sure my birthmark was under it.

“Awesome. I’m Kendall. I go to Hayden Village.”

The private school. That’s why I hadn’t seen her before.

“Coach told us you guys are going to relay with us so we can finally compete in the two hundred,” said Aidy, acting as if she hadn’t just laughed at me a few hours earlier. “After Ellen moved and Lizzie quit for cheer, I didn’t think we’d ever get a good team together, but I am so glad you guys tried out. We’re going to be amazing.”

I dunked my head underwater, getting my face wet, and emerged for air with a smile, adding, “So amazing.” If Aidy was going to pretend nothing had happened, I could too. Bring on the selective amnesia.

Coach Turner blew his whistle and motioned for everyone to get in the pool. As the splashes died down, he sat by the edge of the water, dipping his feet in. “All right, Dolphins. We have three new teammates, so wave your flippers at Lekha, Harper, and John, and give them a warm welcome. We’re going to have a great practice.” Coach skimmed through the papers on his clipboard as the twenty-some members of the Dolphins exchanged “Hi”s and introductions.

“Just a couple of reminders, gang,” continued Coach Turner. “Practice starts at five thirty p.m. Not five thirty-one, not five thirty-seven, and certainly not five forty-five. Five thirty sharp. Be on time to make sure you can beat the other teams’ times. We have a long stretch of practices, and then you’ll have Thanksgiving off and two weeks off for Christmas and New Year’s. I’m not that cruel to make you practice instead of celebrating the holidays with your families.”

As a few kids laughed at Coach’s joke, I realized he had forgotten other holidays, including one celebrated by millions: Diwali. It wasn’t his fault. It was hard to keep up with Diwali. It was based on the lunar calendar, so the dates of the five-day-long festival of lights changed every year, falling sometime between October and November. The worst was when it was the same day as Halloween, or “Diwaleen,” as I liked to call it. Aai would grumble about putting up skeletons and ghosts all around the house when we were supposed to be celebrating with colorful lamps and paper lanterns. This year there was no Diwaleen, though. This year Diwali was next week.

So it turned out Coach would be making me practice instead of celebrating one of my family’s biggest holidays. But I didn’t mind. I always had to go to school and extracurriculars during Diwali here in Michigan. The only time I had ever seen things differently was three years ago when I was in India. Diwali was right before my cousin’s wedding that year.

It was bizarre to be in India and see all my cousins off work and school for a whole week. We went to the theater to see Hindi movies. We went out for ice cream, lit divas, and made powdery patterns of decorative rangoli outside doors. And we exchanged gift envelopes of money every time a new neighbor or relative showed up. It felt totally unreal to see so many people all around me celebrating Diwali with sparklers and nonstop fireworks at night, seeing almost every towering building draped in blankets of holiday lights, seeing all the stores with signs for Diwali sales. None of that happened in our small town, miles away from the large Indian American communities in Metro Detroit, and I’d never explained any of that to Coach, so how would he know?

He blew his whistle, signaling for everyone to get into their own lanes, based on what they were swimming. Harper, Aidy, Kendall, and I were in lane three. The order for the relay was different from the individual medley, so I was eager to find out what I was going to swim.

“Harper, you’ll start us off with the backstroke. Kendall, you’ll stick with breaststroke. Aidy, I’m moving you to fly, and Lekha, you’ll be freestyle.”

Aidy gave a small, sulking hop in the water. “But I always swim anchor.”

“I know, Aidy, and you’ve always made up more than enough time for everyone. But Lekha had an incredible swim at tryouts. Her freestyle was the fastest time in the under twelves. If she can replicate that at a meet, no one will be able to touch you guys. So, come on out, team. Support each other. Remember that teammates stick together. And let’s do this.”

I put my elbows on the slimy tiles at the pool’s edge and pulled myself out of the water. I knew it was best to stay quiet if I wanted to get on Aidy’s good side, if I wanted to fit in. So instead of telling Aidy that Coach was right and I deserved this spot, I pretended my swim cap needed adjusting, focused on my feet, and steadied my chattering teeth. Anything to avoid the icy stare from Aidy that was making me feel colder than I already was.

I backed up, almost bumping into the assistant coach, letting Kendall go ahead of me. Harper got in the pool, hands holding the edge, in position to start the backstroke. The whistle blew. She flung herself back into the pool and began to kick her way to the far end. She tapped and turned back toward us. The water seemed to slide away from her, creating a diagonal pattern off her swim cap. As she tapped the side of the pool we were on, Kendall dove in over her, swiftly doing the breaststroke.

“Faster, Kenny!” shouted Aidy. “You’re slowing us down!”

“Give her a sec, Aidy. New teams take a few practices to gel,” said Coach gently, checking the clock.

“She’s always been on breaststroke. I’m the one doing something totally new.”

Aidy dove in as Kendall tapped the edge. Her butterfly was fast. Much faster than mine. From the starting block, I watched as Aidy splashed through the pool, turned, and made her way toward me. My belly began to flutter and my palms started to sweat. Aidy tapped the edge and I dove in.

My arms cut through the water as I kicked forward. I tried to focus on my form as I turned, but all I could think about was that I had to show Aidy how good I was. I felt more and more nervous with each arc of my arms, until I finally tapped the wall, back with my relay team.

“A couple of seconds off, kiddo,” said Coach Turner. “Keep practicing. You’ll get it,” he added as he headed to the next lane.

My time was more than a couple of seconds off. It was almost six seconds off. I had choked. Instead of swimming the anchor leg, I had let Aidy get into my head so badly, it was like I had swum with an anchor tied to my leg.

Aidy’s face was so red, she couldn’t even speak. Kendall seemed to be relieved Aidy was focusing her anger on me instead of her. And Harper just gave me a look of pity as I treaded water in the pool, my team looking down at me. All I could do was stare at the pool water, where I had failed my team. Where was that selective amnesia when I needed it?

chapter NINE

I tried not to think about my disastrous practice the rest of the week and concentrated instead on cobwebs and dust. The five days of Diwali were kicked off with a weekend of nonstop cleaning, with breaks for homework and meals.

“Everyone has a clean house for Diwali, and we aren’t going to be any different,” said Aai, having just returned from Avantika’s house and seeing all their boxes unpacked and belongings put away.

So Dad was forced to go through his months-old mail mountains that were placed between all the plants in the Jungle. Aai vacuumed. And I was on cobweb-demolition duty, apologizing to each little blond spider as I destroyed its hard work.

Maybe I could write an op-ed about spiderwebs, I thought as I finished removing the sticky cobweb curtains in the basement near Dad’s picture of the lotus-shaped Baha’i temple. That would for sure spare me the front page of the paper early next year when mine was due. If only I could think of a point of view. Was I pro-spiderweb or anti? I wondered as I headed past the kitchen counter with our devghar on it, wiping it off, dusting around the idols.

When Aai worked at her engineering job, we briefly had a cleaning lady. But one day Aai found a four-inch silver idol of the goddess Lakshmi in the trash. The cleaning lady said she thought it was an old action figure so she’d tossed it, and Aai decided to never again have a stranger cl

ean the house.

With our home now as spotless as Avantika’s, and Dad’s mail mountains now more like mail hills, our house was finally Diwali-clean. Dad and Aai started making dinner and Diwali faraal, the sweet and savory fried snacks munched on throughout the holiday.

I watched as Dad churned the handle on the stainless-steel tube of the chakli maker over a small kadhai, an iron bowl that was filled with oil for frying on the stove. The chakli maker pressed the dough made from lentil and rice flours into a star-shaped noodle that Dad then swirled into a spiky pinwheel in the crackling oil.

Aai was cutting diagonal lines into two rolled-out masses of dough that looked like misshapen continents. One was savory dough spiced with carom seeds. The other was sweet dough. She prepped the diamond-shaped khari shankarpali and shankarpali for frying next.

I licked my lips, impatient for the meal, as I did the rangoli. The decorations made of colored powder, flowers, bangles, or lentils and grains were put outside doors and in the house for Diwali. I was making Ganpati out of yellow mung, using white basmati rice for his tusks and red lentils for his pants and crown. Aai had already made an intricate rangoli design using rice she had dyed with plant-based food coloring. It had purple and green paisleys and red flowers. In the center was a large swastik made out of baby bangles.

This was Aai’s favorite design. It was painted at the doorway of her house and several homes in her neighborhood. It stood for luck and for God. It reminded her of home and of making large swastik rangolis with her aai in India when she was a kid. It was a huge, ancient Hindu symbol of auspiciousness from thousands of years ago, used in pujas, weddings, and holidays, found in temples and in almost every Hindu home. My relatives even gave me gold swastik necklaces when we visited them. But despite what it meant in India, I had to beg Aai to stop putting it on the porch in Michigan, because the symbol had been turned diagonal by Hitler and now had a terrible meaning everywhere besides India. I was tired of explaining to Noah that we weren’t Nazis. And I was embarrassed at seeing the horrified looks on trick-or-treaters’ faces during Diwaleen when they saw the swastik on the porch. So Aai finally moved the design indoors a couple of years ago.

With my rangoli done, I started stringing Diwali lights up on the master bedroom window. Aai and Dad’s room faced the street, and I loved how the lights looked from outside. I steadied myself on a stepstool and twisted the lights around the silver tinsel with dangling paisleys that Aai had already put there, cherished decor from our last shopping expedition in India during Diwali.

I plugged the lights in and marveled at the pink, green, orange, and blue reflections of the little blinking lights on the silver tinsel garland. The lights were lit. The rangoli was done. The sounds of oil popping and sputtering from the kitchen danced near my ears. And the smells of carom seeds and fried dough wafted in the air. I beamed, a happy, peaceful feeling coming over me as I took in the wonder of Diwali.

* * *

The next day in English class I was dressed in the nonfestive outfit of a fuzzy alien-green sweater with gray corduroys, my hair over my bindi birthmark. Avantika was wearing real gold bangles and an olive-green sweater with a mustard-yellow odhani with gold sequins and orange flowers embroidered on it. And on her forehead, she had an actual bindi.

“Happy Diwali, Lekha and Avantika,” said Mr. Crowe, putting his hands together in a namaste that made me feel really embarrassed for him.

“Thanks,” I said, anxiously crossing and uncrossing my feet under the desk. I knew what was coming next. It happened whenever a teacher remembered it was Diwali, which, annoyingly and yet thankfully, wasn’t often. It was time for Ambassador Lekha, representing the great land of India, to give a lecture on a holiday celebrated differently by millions of people in thirty seconds, the maximum amount of time people could politely pretend to be interested in stuff that made no sense to them.

“So how about you tell the class a little about your holiday, Lekha?”

There it was. “It’s the festival of lights,” I responded, turning to Noah, who gave me a somewhat supportive shrug-smile. “It’s also some people’s new year.”

“It isn’t everyone’s?” Emma asked from the back.

I bit the inside of my cheeks. Another question meant another minute that my torture was prolonged. But I had no answer to this question because I had no idea why. All I knew was that for my family, the new year was in the spring, during a holiday called Gudhi Padwa.

“India is really diverse, with lots of religions and traditions,” said Avantika, playing with her odhani. “Each state speaks a different language, in addition to English, and they have their own customs. So while the Hindu new year does start during Diwali for some people, it doesn’t for others. Like, it is the new year for my Gujarati side but not for my Marathi side.”

Liam snorted from the back, and I tried to send a telepathic note to Ambassador Avantika to stop her speech, since no one here knew what she was talking about.

“Do you have a question, Liam?” asked Mr. Crowe.

“Nope.”

Avantika ran her fingers through her shiny hair, bangles jingling as she continued. “Several different religions celebrate Diwali. In Jainism, Diwali is the day Bhagwan Mahavir attained moksha, the end of the cycle of rebirth.”

I avoided everyone’s glances and stared at Avantika as hard as I could, trying to get her attention. Hello? Earth to Avantika. Stop the speech.

“Many Hindus celebrate it as Ram’s return from exile after defeating the demon king, Ravan.”

Can you hear me? Is this thing on? I cleared my throat loudly, but the ambassador still had to give her concluding remarks.

“Basically, in many of the different ways to celebrate Diwali, it is a celebration of good over evil, symbolized by lighting lamps. That’s why it is the festival of lights.”

“Is that why you’re wearing your dot today?” asked Liam from his desk.

“Yeah, it is. And it’s not a dot. It’s called a ‘tikli’ in Marathi. It’s called ‘chandlo’ in Gujarati. It’s called ‘bindi’ in Hindi. It’s called ‘kumkuma’ in Kannada,” she replied.

“It’s called ‘fashion’ in American, Liam. You wouldn’t get it,” retorted Harper. “I think it’s neat.”

Neat. She thought it was neat. But in all the years I had gone to school here, no one ever spoke up to stop Liam or anyone else from making fun of the “bindi” I couldn’t take off. My cheeks burned and I blinked away some tears that were trying to spill. I opened my notebook as Mr. Crowe thanked Avantika and began to teach us about thesis-paper structure. Not even bothering to make my favorite cow drawing in the margins, I pushed my pencil hard into the paper as I took notes, feeling far less like a welcome ambassador and more like a total outcast.

chapter TEN

The first two days of Diwali flew by with the same old, same old at school and at home. I could never keep track of what was supposed to happen on those days or even what they were called. To remember, I had to glance at the Kalnirnay and read the Marathi words really slowly. It was the vertical calendar on long paper that listed the million holidays in India from lots of different religions, and had cheesy ads for biscuits and fairness creams at the top. The only difference from normal days was that Aai would do longer pujas for the holidays and the house would fill with the earthy perfume of her all-natural, synthetic-fragrance-free sandalwood incense sticks during her prayers.

But the third day of Diwali was different. It was Lakshmi Pujan, the biggest day of Diwali for us. I showered after school, like we had to before going to the temple or doing a puja at home. I got dressed in my swimming suit and warm-ups for practice. Then I began turning lights on all around the house to welcome the goddess Lakshmi into our home. I turned on the lights under the upper cabinets in the kitchen. Aai lit the oil lamps with long wicks she had made by rolling cotton out into worms, like when you played with clay.

“You’re dressed like that for puja?” she asked softly, eyeing my warm

-up suit. Aai was wearing a gorgeous purple sari with gold embroidery. The padar, draped over her bare midriff and pinned onto the shoulder of her sari blouse, flashed magenta or gold, depending on how the light hit it.

I could tell she was sad. Her voice always got soft when she was sad.

“Back in India we wear our nicest clothes and gold jewelry for Diwali, and you’re in your Halloween costume.”

“It’s not my costume,” I said, turning on the chandelier lights in the formal dining room next to the kitchen. “I mean, it was. But today it’s for swimming practice.”

“In India you wouldn’t have had swimming practice. Schools and classes are all closed for the holidays. And some of the biggest Hindi movies of the year open during Diwali.”

“Well, we don’t live in India. We live in Michigan. And it’s just a normal day here. Remember?” I added, turning on the family room light.

“What do you think it is, Diwali?” asked Dad, entering the kitchen dressed in a pink kurta and white salwar.

“Hilarious, Dad,” I said, trying not to smile. But it was kind of funny for him to say it on Diwali, when all the lights were on in the house on purpose.

“Let’s start puja before your practice,” said Aai as we all stood in front of the little temple on the kitchen counter. “Hurry, or we’ll be late.”

A piece of jewelry from each family member was put into a plate alongside silver coins with the goddess Lakshmi on them, and some dollar bills. Aai drew a swastik out of red kunku and water on the counter. As the prayer began, I watched the diva’s flame flicker against the silver image of Lakshmi. I put some flowers from the Jungle before the gods and then did namaskar.

When it was all done, I gobbled down the prasad Aai had made, besan laadus. I definitely ate more than my share of the sweet chickpea-flour laadus, but, hey, prasad was food that was offered to God first and then eaten, considered blessed. And I figured I needed more blessings and luck than Aai and Dad. After all, they weren’t the ones who had to go to school with Liam or swim with Aidy.

American as Paneer Pie

American as Paneer Pie